Virginia Woolf

-Country: United Kingdom

-Dates: The suicide was committed in March 1941, when the writer was 59 years old. The letter addressed to her husband Leonard dates from 18th of March; and the letter to her sister Vanessa, from the 23rd of the same month.

-Description of case:

This case deals with the suicide letters of Virginia Woolf, the British writer considered one of the leading writers of 20th century avant-garde modernism and of the feminist movement. Virginia Woolf, whose full name is Adeline Virginia Stephen, was born in London the 25th of January 1882. She devoted her life to the writing of novels, short stories, plays, and other literary works such as essays. Some of her most famous works are ‘Mrs Dalloway’, ‘To the light house’ or ‘A Room of One’s Own’; the last one being an essay on the presence- or rather lack of presence- of women in literature, a space dominated by men. She reflects on the inequality and injustice that women experience simply because they are women and presents the difficulties that a woman writer must face, stating that “A woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction” (A Room of one’s own).

Virginia Woolf had a life marked by traumatic episodes such as the prompt death of her mother and of her half-sister or the sexual abuse by her stepbrother. All of that caused her to suffer from depression, with long periods of emotional instability. For this reason, she attempted to take her life on several occasions: the first one in 1904 and the second one in 1913. Finally, in 1941 (at the age of 59) she drowned herself by walking into the river Ouse with her pockets full of stones. But before taking this action she wrote two letters, one of them to her sister and the other one to her husband.

At the time, the press speculated about the motives of her death, going so far as to say that the author was not able to withstand the atrocities of World War II.

Anyway, although the motives of her suicide were not clear, the truth is that its veracity was never questioned. Nobody believed that her death concealed a murder disguised as suicide, but everybody believed that she was the one who decided to commit suicide on her own will, without being coerced by another person.

In the same way, the two suicide letters were taken as genuine and were not inspected at the time, which means that forensic linguistics was not involved and, obviously, that the case was not brought at court.

This is not surprising since (apart from the fact that there was no need of examining the letters since it was clear that Virginia Woolf committed suicide and there was no crime) the discipline of Forensic Linguistics was born later. It appeared in 1968 when the linguist Jan Svartvik analysed a series of statements supposedly made years before by John Evans, who was condemned for the murder of his wife and his baby and was hanged. Jan Svartvik demonstrated that they were false, which would mean that Evans was innocent, and that linguistic analysis could be used as evidence at a court law.

Nevertheless, during the last decades, the suicide letters of the British author have awakened the interest of many linguists who had aimed to prove (or to confirm) their authenticity by doing an analysis of the language at different levels. Furthermore, the examinations of the letters may help to stablish the real reasons Virginia Woolf had to commit suicide, avoiding in that way any false suppositions.

Hence, the union of different existing studies of the letters in this post will help us to draw conclusions about the case.

-Category of the case:

This is a case of authorship attribution, or rather, “a method of authorship recognition” (Hänlein as cited in John Olsson, 2004) since it is not a matter of searching for an unknown author but of trying to recognise if the given name corresponds with the actual author or not.

Most of the suicide notes are signed by the writer as the purpose of them is usually that of allowing the victims to bid farewell to their loved ones or to provide a justification of the motives of their suicide, among others.

Hence, forensic linguists have already a name, an individual, as the alleged author of the letter and in parallel as the suicide victim. Their role is that of proving if the letters are genuine or not.

Virginia Woolf’s suicide letters to her husband Leonard and her sister are signed with the name “Virginia” and the first initial “V” respectively, which makes the linguists start from a base: the authorship of the letters is attributed to Virginia but, is that true?

As the different forensic studies carried out on this issue have demonstrated, the answer to this question is: Yes, it is!

-Materials/Documents examined in the case.

The materials examined in the case by the different linguists are the suicide letters that Virginia Woolf left, which can be found in Forensic linguistics analysis of Virginia Woolf’s suicide notes by Ni Luh Nyoman Seri Malini and Venessa Tan (attached in the appendix).

In addition, although the analysis of the notes is uniquely linguistic, I think that a previous knowledge of the biography of the writer is helpful to understand the context and make the study easier (and probably, the linguists had this information).

In order to write this article, I have recurred to some websites (whose link I will specify in the last section) which I have found quite useful and which I encourage you as the reader to visit.

-Study of the case:

Aims of the linguists:

When encountering a suicide letter, the first question probably made by the linguists is if it is really a suicide letter.

The epistemic genre may allow the author to write about his/her most intimate feelings and thoughts, especially when it is written using the first person singular. Hence, linguists should clarify if the letters found are just personal letters or if they are indeed suicide letters.

In the case of the suicide letters of Virginia Woolf the answer was clear since the letters were accompanied by the implementation of the action: Virginia not only talked about her mental state and communicated her desire to take her own life, but she was found dead in the river Ouse.

Furthermore, another task of linguists was to determine if the letters were written by Virginia Woolf herself, and therefore, they are genuine. As it has been stated before, the letters were signed by the British writer herself, so the linguists hypothesised that she was the real author.

Finally, by the analysis of the notes, linguists pretended to ‘read between the lines’ and detect the real motives of her suicide.

In order to demonstrate the previous points, different linguists have carried out an analysis of the letters at different levels, paying special attention to lexical semantics and pragmatics.

Linguistic analysis, methodology and discussion:

The methodology used to analyse the letters varies according to the linguists involved in the case. Whereas some of them conduct a human based study (that is, a study that consist of analysing the letters by means of doing detailed re-readings, close readings, etc.), some others use computer software such as the Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count (LIWC) program to analyse the letters. This program “counts the frequencies of each word in the given text(s) and calculates the percentage of categories to which various words are classified in the given text(s)” (Yong-hun Lee and Gihyun Joh, pp. 178). Furthermore, some linguists resort to the comparison of Virginia Woolf’s letters with other texts, whether by the author herself or by another author.

Andrea Martínez compares the suicide letters of Virginia Woolf with genuine suicide letters written by other women. In that way, she tries to use as data linguistic corpora that is as similar as possible. The materials belong to the same genre-epistemic- and although the range of age of the authors is quite varied, their gender is the same (all of them are female) and they are all English native speakers.

Andrea Martínez is concerned with “what lies in a suicidal person’s mind before ending his/her life” (“Andrea Martínez, 2018, pp 2). She recognises among the suicide victims the experience of traumatic situations which may cause them, for instance, to have feelings of guilt, frustration, or emotional detachment. Virginia Woolf’s notes share some of these characteristics, which lead the linguist to conclude that they are indeed suicide letters.

On the other hand, Yong-hun Lee and Gihyun Joh decided to compare the suicide notes by Virginia Woolf with some of her literary works, among which we can differentiate three novels-The Voyage Out, Night and Day and Jacob’s Room– and one short story –Monday or Tuesday.

Their study was focused on the lexical semantics of the texts since it can help to identify them as suicide or non-suicide written works. Thus, having clearly defined non-suicide texts (that is, her literary works) they wanted to test if the two assumed suicide letters shared their linguistic properties or rather, they presented differences. They used the LIWC program so that different semantic types of words were grouped and a statistic of their frequency in the texts was given.

Some of the patterns created by the computer program were I words (which refer to first person pronouns such us ‘I’, or ‘we’), positive emotions (based on the verbs, nouns, and adjectives used like “happy”, “loved” and “good” and negative emotions (seen in the words ‘mad’ and ‘horror’), cognitive processes ( seen by the words used in “I think you know”), authenticity (“refers to writing that is personal and honest”), emotional tone (which is interpreted as higher in the statistics if there are more positive words than negative), analytic (which “refers to analytical or formal thinking” or clout (which refers to linguistic interventions that are “authoritative, confident, and exhibits leadership” (Malini, N. L. M. S. & Tan, V, 2016, pp. 53-54).

The results of the study revealed much higher values in the suicide notes of the I words, positive emotions and cognitive processes statistics; and much higher values in the literary works regarding the analytic and clout statistics. The value of the rest of the groups of words were quite similar. (Yong-hun Lee and Gihyun Joh, 2019, pp. 178).

According to Newman, Pennebaker, Berry, and Richard’s investigation on lying behaviour (2003), “when the participants were lying, they used more negative emotions and fewer first-person singulars” (N,P,B,R as cited in Malini, N. L. M. S. & Tan, V, 2016,pp. 54). Hence, the results, which showed that the assumed suicide notes have a positive emotional tone and a repeated use of I words, prove that the suicide letters of Virginia Woolf are not feigned but they are genuine.

Moreover, lexical semantics may help to create a profile of the psychological state of the writer. The use of negative words such as “disease” or “mad” by the writer may make reference to depression and may reveal that she was aware of her situation (probably because she had had previous depressive episodes). In addition, the presence of a great number of positive words such as “good” or “happier” with the coexistence of negative words such as “terrible times” or “horror” (although they are not overly significant, they are still high in number) may support the idea advocated by some psychologists that the writer suffered from bipolar disorder, which was probably caused by her depression. (Malini, N. L. M. S. & Tan, V, 2016, pp.56).

Regarding their structure and content, the letters follow the common characteristics of suicide letters presented by John Olsson. Firstly, they “contain an unequivocal proposition” which is “thematic (…), direct (…) and relevant to the writer’s relationship with the addressee”. It can be seen in both letters since she starts with a direct proposition stating she is ‘going mad again’. Moreover, the use of the adverb ‘again’ implies that it is something that happened before, and that the addresser should know it so there must be a relationship between addresser and addressee. Secondly, they present the act of committing suicide as “the only course of action”, which is reflected when Virginia states: ‘I have fought against it, but I can’t any longer’. Finally, Olson clarifies that “genuine suicide notes tend to be short”, another criterion that is satisfied since we are dealing with two letters which are 192 and 166 words in length (John Olsson, 2004, pp. 162).

With the previous studies, the linguists demonstrate the letters’ genuineness and Virginia Woolf’s mental state at the time of writing the letters. From now on, the focus will be on the pragmatics of the text, which may help to decode (together with the conclusions drawn thanks to the lexical semantics analysis) the real motives for her suicide.

Pragmatics is used to see not only what is said but also what is meant according to the context. Linguists have resorted to the Speech Act Theory (Austin 1962) to establish which are the illocutionary forces that predominate in the letters. The main findings have been that there are a great number of representatives and expressives that are highly connected with explanatory and accusatory constructions. (Andrea Martínez, 2018, pp. 14-15).

Virginia Woolf states in the first two lines of each letter that she thinks she “is going mad again”. With these declarative sentences she starts by explaining why she is writing that kind of letters. She appears to feel unable to perform some activities such as writing or reading (perceived when she says “I can’t even write this properly” or “I can’t read”) and she states she “hear voices”. These are symptoms that can be linked to depression and bipolarity (Malini, N. L. M. S. & Tan, V, 2016, pp. 55). So, it could be said that one of the reasons that made her take the decision of walking into the river Ouse was her mental state. She knows her situation since she has experienced similar episodes before and she does not want to live it again (“I shan’t get over it now”).

Another motive linked to the previous one is the fact that she felt guilty and could not bear this feeling. People suffering from depression often have a damaged self-esteem which leads them to feel a burden to others. Virginia Woolf believed that she was “the reason why Leonard did not become a better writer” (Andrea Martínez, 2018, pp.13). It can be inferred from the sentences on the letter to her husband: “I know I that I am spoiling your life, that without me you could work” and “I can’t go on spoiling your life any longer”. So, she decided to take her own life and argued that without her, her husband could make progress.

Virginia Woolf felt that it was her duty to sacrifice her life. She considered it was the better path to follow and she wanted to show she was sure of it. It can be observed since she says she “can’t write (…) properly” but nevertheless she writes a coherent and cohesive letter. Furthermore, she wants to emphasize the seriousness of her situation and she “changes from: ‘‘I feel certain’’ to: ‘‘I am certain’’; from an expressive to a representative, i.e. from a feeling to a fact” (Andrea Martínez, 2018, pp.15) to convince the reader that she is sure she is going through a mental breakdown and she cannot bear it.

The fact that the writer showed knowledge of the language and a great domain of the writing techniques supports the hypothesis that defends the authenticity of the authorship of the letters (pointing to Virginia Woolf, a brilliant writer of the time).

-Comparison other letters by the author:

The magnificent writing of the letters is not the only aspect that can serve as proof of authorship. Another possible study may consist of the comparison between the suicide letters and other letters by the author for the purpose of finding possible similarities in the style since “every native speaker has their own distinct and individual version of the language they speak and write, their own idiolect” (Halliday et all. and Aabercrombie, as cited in Malcolm Coulthard, 2004. Pp 431). Hence, if the suicide letters and other letters by Virginia Woolf share a considerable number of linguistic characteristics, it would mean that they belong to the same author and, therefore, they are genuine.

The letters chosen to be compared are three letters addressed to the writer Vita Sackville West. The reasons why they have been selected are that, in the same way as the suicide letters (which were addressed to Virginia Woolf’s husband and sister), these are personal private letters addressed to someone with whom the author had a close relationship. It is said that Virginia Woolf and Vita Sackville had a romantic relationship, which explains the intimate tone of the letters. Furthermore, they are short in length (they have 116, 203 and 114 words whereas the suicide letters have 192 and 166).

Among the lexical similarities found, we could highlight the use of identical or resembling greeting expressions. In the two suicide letters, the writer uses the term ‘Dearest’ to initiate the writing. In one of the letters to Vita Sackville, Virginia uses the same expression and in the other two she starts with ‘My dear Vita’ which, although is not exactly the same expression, contains the word ‘dear’ presenting a close connection. Another common aspect is the abundant use of intensifiers. The letters to Vita contain ‘extremely’, ‘very’ or ‘really’ and the suicide letters have some as ‘incredibly’, ‘astonishingly’ or ‘perfectly’. Furthermore, the adjective ‘certain’ is repeated in both suicide letters (together with the noun ‘certainty’) and in one of the letters to Vita. The recurring use of this word and its preference instead of other synonyms such as, for example, sure, may indicate that it is a frequent word in the writer’s speech.

Continuing with the lexical similarities, all the letters have words that can be classified as negative or positive ones. Some of them coincide or are from the same lexical family. The letters to Vita include positive words such as the verbs ‘like’ or ‘enjoyed’ and nouns such as, for example, ‘affection’ and ‘niceness’. The suicide letters contain the verb ‘loved’ and nouns such as ‘happiness’ and ‘goodness. On the other hand, among the negative words, we can highlight in the letters written prior to her death, the verb in its progressive form ‘spoiling’; nouns such as ‘horror’ and ‘disease’; and adjectives such as ‘mad’ or ‘terrible’. In the letters to Vita, Virginia uses the verbs ‘annoyed’, ‘hurt’, ‘worries’ and ‘dislike’; some nouns such as ‘pain’, ‘flu’, ‘nuisance’ or ‘abuse’; and adjectives such as ‘horrid’, ‘idiotic’, ‘exacting’. The negative words stand out in particular since there can be seen some connections among them. The words ‘horrid’ and ‘horror’, used in each of the types of letters, belong to different categories but they are formed from the same base. Furthermore, some words may form semantic paradigms: ‘flu’- ‘disease’, ‘mad’- ‘idiotic’ or the verbs (here written in their base form) annoy, hurt and spoil.

Another similarity found is the frequent use, considering these are short letters, of grammatical processes to assign focus. It could be a distinctive feature of the author’s writing style. Just in a few lines, we can see the processes of clefting and fronting on several occasions. In the letters to Leonard, there are two examples of fronting: ‘that without me you could work’ instead of the unmarked order consisting of Subject + Verb+ Adverbial (>that you could work without me) and ‘And you will I know’ instead of the sequence Subject + Verb+ Object (>and I know you will). In the letters to Vita, it can be found: ‘Here I am’ instead of the unmarked order (>I am here). Cases of clefting, on the other hand, are not so easy to spot since they do not follow the conventional pattern for clefting- It + BE (in any of its forms) + X + that/ wh-word (Cl)– but they can be classified as subtypes of the phenomenon. In the letter to Leonard, it can be found the pseudo cleft structure ‘What I want to say is’, consisting of: Wh-word (Cl) + BE +(that) + X. In addition, a particular structure of clefting imposed by the wh-word ‘how’ appears both in the letters to Vanessa, Virginia Woolf’s sister, and to Vita: ‘how I loved your letter’ and ‘how one worries in bed’ or ‘how much I depend on you’.

By resorting to a pragmatical study and focusing on the last letter written to Vita, since it is the one that is closer to the date of her death, the reader could deduce Virginia Woolf blames herself in the same way as she did in the suicide letters. It is reflected in the use of some representatives such as ‘I said something idiotic’, ‘perhaps said something that hurt you’ or ‘I’m being (…) foolish and exacting’. Furthermore, she seems to feel vulnerable, and she shows dependency on the people around her. It is reflected on the sentence she writes to her husband: ‘If anybody could have saved me it would have been you’, which positions him as responsible for his wife’s fate. In the case of the letter to Vita, Virginia Woolf is more direct and states ‘I depend on you’.

Since the letters to Vita were written approximately one year before she composed the suicide letters, it can be said that they give a clue about the progression of her mental state, which seemed to be already damaged by that time. The use of certain words may support this idea. An illustration is ‘flu’ which may make reference to depression as it occurs in the suicide letters when she uses the phrase ‘terrible times’.

Hence, all the similarities explained help to construct an idiolect that points to Virginia as the author of all the notes.

-Any other linguistic aspect relevant to the case:

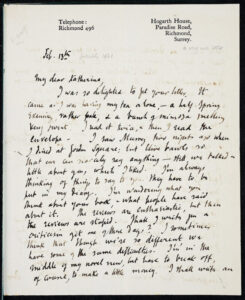

A linguistic aspect that has not been studied closely and that I consider quite relevant (since the original suicide letters, handwritten by the author, are available) is graphology. The handwriting of the suicide letters could be compared with that of other letters or notes written by Virginia Woolf in order to see if they are similar.

Although this work is competence of the graphologists, I would suggest a comparison between the original suicide letter that Virginia Woolf wrote to Leonard and a letter addressed to her friend the writer Katherine Mansfield:

At first glance, it is possible to intuit that they have very similar spellings. Nevertheless, as it has been said before, it would be necessary to draw conclusions a more in-depth study by professionals in this field of study.

-Conclusion:

This is the end of the analysis of the suicide notes of Virginia Woolf. The analysis has demonstrated that Forensic Linguistics intercede in the most unexpected cases.

Forensic Linguistics has served to prove here the genuineness of the suicide letters of Virginia Woolf, as well as to establish the possible reasons of her suicide.

The letters analysed share features with other suicide letters so, consequently, it categorizes them as suicide letters too. Furthermore, the connection of these letters with other written by Virginia Woolf demonstrates their authenticity.

Virginia Woolf’s decision to commit suicide, which took place in 1941- year which falls within the framework of the World War II- was influenced by her mental state: she suffered from depression and, furthermore, some psychologists argue that she also suffered a bipolar disorder.

Since this is a study carried out by many linguists, it provides a very broad view of the issue. By the compilation of many conclusions, we can construct our own. I think that, although the historical context (war) was not the cause of her suicide, as it has been argued by psychologists who had investigated the case, it influenced her mental state. She lived in a hostile atmosphere that did not provide her the peace she needed but it aggravates her situation.

All this said, forensic linguistics is an important tool to analyse suicide letters.

-The case in popular culture:

The case has not been widely publicised since there was no crime involved and, consequently, it was not brought at court and no legal documents were produced. However, the life of the writer with its fatal outcome has been present indeed in the popular culture.

The movie ‘The hours’ by Stephen Daldry starts with the recreation of the suicide of Virginia Woold (embodied by Nicole Kidman), a sequence that is followed by the presentation of two more characters- Laura Brown (Julianne Moore) and Clarissa Vaughn (Meryl Streep)- whose stories will be developed throughout the movie.

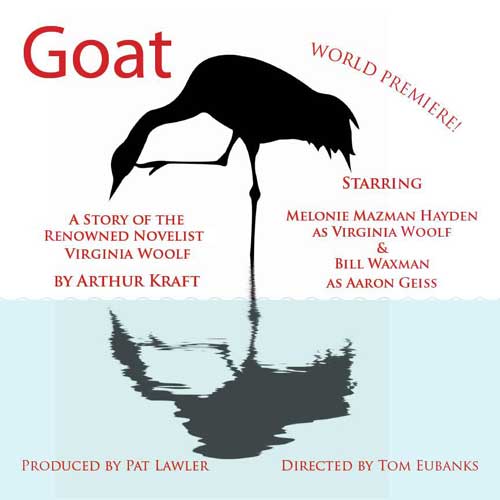

Furthermore, Virginia Woolf has been paid tribute in some other ways: The Elite Theatre company presented ‘Goat’, referring to the nickname that the writer had; and Emma Woolf (Virginia Woolf’s niece) published an article called ‘Literary haunts: Virginia’s London Walks’. Furthermore, there are numerous videos on YouTube that commemorate her death.

- Movie ‘The Hours’ opening scene on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xl08W86Oaqo

- Theatre: https://www.theelite.org/

- YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AEXNs-ty4Dc&t=1s

-Appendix:

Suicide letters:

To Leonard:

18/03/1941

Dearest,

feel certain I am going mad again. I feel we can’t go through another of those terrible times. And I shan’t recover this time. I begin to hear voices, and I can’t concentrate. So I am doing what seems the best thing to do. You have given me the greatest possible happiness. You have been in every way all that anyone could be. I don’t think two people could have been happier till this terrible disease came. I can’t fight any longer. I know that I am spoiling your life, that without me you could work. And you will I know. You see I can’t even write this properly. I can’t read. What I want to say is I owe all the happiness of my life to you. You have been entirely patient with me and incredibly good. I want to say that — everybody knows it. If anybody could have saved me it would have been you. Everything has gone from me but the certainty of your goodness. I can’t go on spoiling your life any longer.

I don’t think two people could have been happier than we have been.

V.

To Vanessa:

23/03/1941

Dearest,

You can’t think how I loved your letter. But I feel I have gone too far this time to come back again. I am certain now that I am going mad again. It is just as it was the first time, I am always hearing voices, and I shan’t get over it now. All I want to say is that Leonard has been so astonishingly good, every day, always; I can’t imagine that anyone could have done more for me than he has. We have been perfectly happy until these last few weeks, when this horror began. Will you assure him of this? I feel he has so much to do that he will go on, better without me, and you will help him. I can hardly think clearly anymore. If I could I would tell you what you and the children have meant to me. I think you know. I have fought against it, but I can’t any longer.

Virginia.

Letters to Vita Sackville West:

Monk’s House

Rodmell

Lewes

Sussex

19 August

My dear Vita,

Have you come back, and have you finished your book- when will you let us have it? Here I am, being a nuisance, with all these questions.

I enjyed your intimate letter from the Dolomites. It gave me a great deal of pain- which is I’ve no doubt the first stage of intimacy- no friends, no heart, only an indifferent head. Never mind: I enjoyed your abuse very much…

But I will not go on else I should write you a really intimate letter, and then you would dislike me, more, even more, than you do.

But please let me know about the book.

Monk’s House

Rodmell

Lewes

Monday [15 September]

My dear Vita,

I like the story1 very very much- in fact, I began reading it after you left…went out for a walk, thinking of it all the time, and came back and finished it, being full of a particular kind of interest which I daresay has something to do with its being the sort of thing I should like to write myself. I don’t know whether this fact should make you discount my praises, but I’m certain that you have done something much more interesting (to me at least) than you’ve yet done…

I am very glad we are gong to publish it, and extremely proud and indeed touched, with my childlike dazzled affection for you, that you should dedicate it to me. We sent it to the printers this morning.

…By the way, you must let me have a list of people to send circulars to- as many as you can. And to do this you must come and see me in London for you should have heard Leonard and me sitting over our wood fire last night and saying what we don’t generally say when our guests leave us, about the extreme niceness etc etc and (I’m now shy- and so will cease.)

Monk’s House

Rodmell

near Lewes

Sussex

19 March

Dearest,

I have a horrid little fear, as you’ve not written, that I said something idiotic in my letter tother day. I dashed it off, I was so glad to get yours, with a rising temperature, and perhaps said something that hurt you. God knows What. Do send one line because you know how one worries in bed, and I cant remember what I wrote.

Forgive what is probably the effect of flu… This is to show why I’m being, as I expect, foolish and exacting. It also shows how much I depend on you, and should mind any word that annoyed or hurt you. One line on a card- that’s all I ask.

-References:

Abercrombie, D. (1969). ‘Voice qualities’ in N.N. Markel (ed.): Psycholinguistics: An Introduction to the Study of Speech and Personality. London: The Dorsey Press.

Coulthard, Malcolm. (2004). Author Identification, Idiolect and Linguistic Uniqueness. Applied Linguistics. 25. 10.1093/applin/25.4.431.

Halliday, M. A. K. (1975). Learning how to mean. London: Edward Arnold.

Halliday, M. A. K., A. McIntosh, and P.Strevens. (1964). The linguistic Sciences and Language Teaching. London: Longman.

Hänlein, H. (1998). Studies in Authorship Recognition: A Corpus-based Approach. Frankfurt: Peter Lang, European University Studies, Chapters 4 and 5.

Lee, Yong-hun & Joh, G. (2019). Identifying Suicide Notes Using Forensic Linguistics and Machine Learning. The Linguistic Association of Korea Journal, 27(2), 171–191. https://doi.org/10.24303/lakdoi.2019.27.2.171

Malini, N. L. M. S. & Tan, V. (2016). Forensic linguistics analysis of Virginia Woolf’s suicide notes. International Journal of Education, 9(1), 50-55. doi: dx.doi.org/10.17509/ije.v9i1.3718

Martínez Celis, Andrea. (2018) A Study of the Linguistic Features of Female Suicide Letters: from the Writings of Ordinary Women to the Writings of Virginia Woolf JACLR: Journal of Artistic Creation and Literary Research.

Newman, M. L., Pennebaker, J. W., Berry, D. S., & Richards, J. M. (2003). Lying words: Predicting deception from linguistic styles. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 29, 665–675.

Olsson, John. (2004). Forensic Linguistics An Introduction to Language, Crime and the Law. New York: Continuum.

Woolf, Virginia. (1929). A room of one’s own. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company.

-Photos:

Photo 1:https://www.latercera.com/culto/2018/01/25/virginia-woolf-siglo-xx/

Photo 4:https://bloggingwoolf.org/tag/arthur-kraft/

Photo 5:https://www.elespectadorimaginario.com/las-horas-al-rescate-de-la-memoria-de-virginia-woolf/

-Links to websites with additional information on the case: